The Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations

Supplement to the Illustrated London News, 24 May 1851

Collection no. H585

In 1851 Hyde Park became home to the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, a spectacular celebration of international manufacturing, technology and design. Although industrial exhibitions had been held in other cities, such as Paris, the idea of an exhibition open to exhibitors from around the world was a novel one. It appears to have been the brainchild of Henry Cole, a civil servant interested in manufacturing and design, and the project really took off when he gained the backing of Prince Albert.

The Great Exhibition building

The Great Exhibition building

Lithograph by G Hawkins, 1851Collection no. H1429

A suitably innovative and ambitious building was required to house the Great Exhibition. Joseph Paxton, the renowned gardener, put forward the winning design. His vast glass and iron structure became known as the Crystal Palace. It covered 18 acres on the southern edge of Hyde Park and was built with incredible speed, in around eight months. It was designed to be temporary and was constructed from prefabricated parts.

Exterior of the south front of the Great Exhibition building

Illustrated London News, 3 May 1851

Collection no. H1449

Paxton had to adapt his design for the Crystal Palace so that it could safely enclose several large elm trees that would otherwise have been felled. In the view of the south front of the Great Exhibition building, shown here, one of the trees is clearly visible inside.

Hyde Park in 1851

Engraved by JB Allen after JD Harding, 1850s

Collection no. H153

The Great Exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria on 1st May 1851 and ran until 15th October. It was a huge success, attracting an estimated six million visits in just under six months. The tickets were initially expensive but were reduced to attract a wider and more diverse audience. The vast majority of visitors were the ordinary people of Britain. They came from all parts of the country with many seeing London for the first time. Excursion trains were laid on especially to bring visitors to the capital and many workers were given time off so that they could attend.

The Great Exhibition also attracted the well-to-do and those from abroad. Celebrity visitors included Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, George Eliot and Alfred Tennyson. William Makepeace Thackeray was inspired to write a poem by his visit and Charlotte Bronte described hers thus: Yesterday I went for a second time to the Crystal Palace. We remained in it about three hours, and I must say I was more struck with it on this occasion than at my first visit. It is a wonderful place – vast, strange, new and impossible to describe. Its grandeur does not consist in one thing, but in the unique assemblage of all things. Whatever human industry has created you find there….

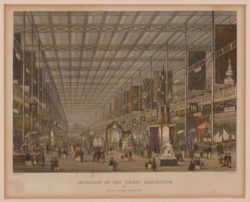

Interior of the Great Exhibition, from the Transept looking West

Chavanne, 1851

Collection no. H1450

The Works of Industry of All Nations were presented by almost 14,000 exhibitors, around half of whom came from Britain with the rest from other parts of the world. Exhibits fell under the broad categories of machinery, raw materials and products. Visitors saw a huge range of items such as an enormous steam hammer, a printing press that could produce 5000 copies of a newspaper in an hour, early photographic equipment and a velocipede (a forerunner of the bicycle). Two of the most popular exhibits were the Koh-i-Noor diamond and a collection of small stuffed animals arranged in scenes, such as kittens at a tea party.

In addition to the wonders of industry, the event featured the first public flushing toilets. Visitors paid 1d to use them – probably the first time that anyone “spent a penny”.

Dogs, smoking and alcohol were banned but visitors enjoyed more than a million bottles of soft drink and nearly a million bath buns.

The Great Exhibition influenced many aspects of society, including art and design education, international relations, trade and tourism. It was also a financial success, making a considerable profit. The money was used to purchase land in South Kensington and establish there a number of institutions including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum, the Natural History Museum, Imperial College, The Royal Colleges of Art and Music and the Royal Albert Hall.

The Crystal Palace, always expected to be sited temporarily in Hyde Park, was sold to a private company who moved it to Sydenham. The nearby residential area was renamed Crystal Palace after the famous landmark. The building was destroyed by fire in 1936.